Rarely does the Western world highlight artistic traditions of the Islamic world. Often, European art is viewed as a kind of standard for high culture. However, the richly varied history of Muslim artists deserves to be examined more closely, especially contemporary artists who have both exemplified traditional forms and pushed the envelope of change. In Pakistan, one of the most famous contemporary artists to have ever lived is Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, known mononymously as Sadequain (1923-1987). An artist of many mediums, Sadequain’s work often combined calligraphic lettering with imagery of real, everyday life; through these, he expressed his lifelong search for truth and meaning.

Sadequain was born to a family of calligraphers in Uttar Pradesh, India, and showed signs of artistic talent from an early age. He worked as a calligrapher and copyist at All India Radio for some years as a young adult before he was eventually discovered by politician and art critic Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, who invited him to curate a solo exhibition. Thus, his career took off to new heights, and soon his works were being displayed in cities the world over, from London to Damascus.

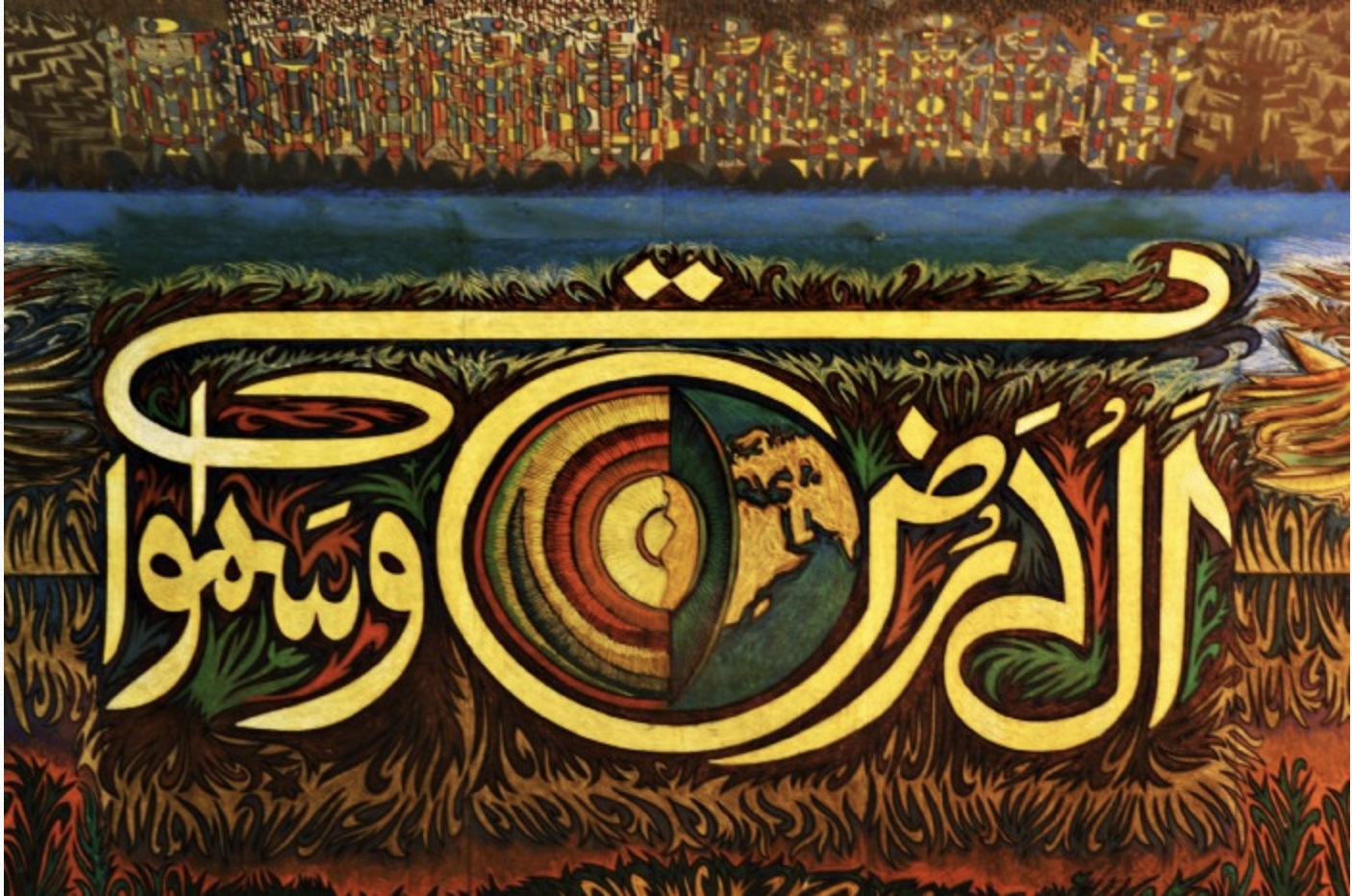

He was well known for his calligraphy, which interpreted verses from the Qur’an or poetry into vivid, sweeping brush strokes. Often, he manipulated the script into striking shapes: marks reaching towards the sky, encircling planets, rising and falling like mountains. This versatility contributed to the expressive nature of his art, which also made it resonate with a great many people.

Many of his mural paintings adorn public buildings all over Pakistan and India. One notable work is the mural at Lahore Museum entitled “Evolution of Mankind”, which was originally painted for the ceiling and depicts a plethora of celestial bodies as dense circles of vivid color. The mural represents a verse from Allama Iqbal, a famous Urdu poet, which translates to: There are other worlds beyond the stars. The dynamic and organic shapes evoke a sense of constant rotation and flow. Another of his murals adorns the ceiling of Frere Hall in Karachi, featuring elaborate calligraphy running alongside the edges; unfortunately, he passed away before its creation.

Besides mural work, Sadequain was also a prolific painter, producing hundreds of canvases over his lifetime. In various series of artworks, he examined both themes of everyday life and the sublime; subjects of his art ranged from ordinary laborers to dramatic renditions of the crucifixion of ‘Isa (A). In one series he used the hardy cactus plant as a metaphor for resilience, with strong, rippling strokes of dark color. In another, swathes of cobwebs became a symbol for the worldly absurdities that cloud and paralyze the human mind and spirit.

In his home country of Pakistan, Sadequain is considered a national treasure and a trailblazing artist. His work contributed to a renaissance of Islamic-inspired and calligraphic art, and a newfound appreciation for the versatility of the Arabic and Urdu scripts.

(Pictured: A panel of Sadequain’s last mural at Frere Hall in Karachi. The mural spells out Arz-o-Samawat, or the Earth and the Skies)