“It’s a little chilly out, huh?”

The female officer’s attempt at small talk did nothing to ease that fearful pit in my stomach, the one that black and brown folks get when they see a police cruiser pull up behind their cars or slowly roll along next to them when they walk down the block. I felt a twisting, churning knot from my stomach, resulting from a combination of fear and anxiety from knowing that many of these encounters leave dark bodies lying dead in the streets or result in physically and emotionally scarring arrests that perpetuate the idea that only people of color commit crime.

I knew exactly why she was small-talking me. I was a Muslim and I had prayed in public.

—–

Prayer, or salah, is one of the five pillars of Islam. We submit ourselves to Allah (May He Be Glorified and Exalted) five times a day, bowing and prostrating ourselves in the direction of the Ka’ba . These five prayers should be performed at specific times, which for many Muslims, can be easily found online or on smartphone apps. These prayers are not only a way for us to submit ourselves to Allah and keep Him in constant remembrance (dhikr), but also a way for us to give thanks and communicate with Him frequently.

As can be expected, many times we are not able to pray exactly at the correct time, whether we are caught up at work, in class, traveling, etc. It is generally accepted that we can make up these prayers as soon as we are able to. This is why you often find us praying all throughout the day, at various times behind Kerckhoff Hall.

As a very recent convert to Islam, I have had several lively discussions with my brothers and sisters concerning public prayer. My experience is that the Muslim community is fairly split as to whether we should pray in public spaces. On one hand, being a Muslim in the US has a very racialized, xenophobic meaning, particularly after 9/11. By praying publicly, we place ourselves in a position to experience racial profiling and bigotry by certain individuals who woefully misunderstand our religion. So many feel it’s better to pray at home or in a safer space. On the other hand, many Muslims feel that our obligation and civil right to pray in public supersedes racist and xenophobic reactions, and that we as a community should not feel afraid to pray publicly. I have personally practiced both; I’ve prayed pre-dawn (fajr) prayer in Union Station, mid-day (dhuhr) prayer on a Caltrain platform in San Francisco, and afternoon prayer (asr) in front of the National History Museum. I’ve also made the decision to wait until I got home or to campus to pray because of large crowds or because there was a lack of private or clean space to lay my prayer mat. I’ve also avoided public prayer because I’m aware of how my appearance has been racialized as being suspicious and violent as a brown, bearded male. Ultimately, the decision to pray publicly is rarely an easy one.

—–

I got to the Tustin Metrolink station at about noon, in preparation for the 12:16 train back to Los Angeles. An electronic banner notified riders that the train to Los Angeles was running 15 minutes late. I had yet to pray mid-day prayer (dhuhr), and realized I had plenty of time to pray before the train arrived. Before we pray, Muslims ritually cleanse and purify ourselves (wudu) by washing our hands, face, arms and feet. I quickly walked over to the gas station across the street to use the bathroom and returned to the station. I set up my prayer mat facing the Ka’ba on the long ramp adjacent to the station, away from the tracks and pedestrian traffic. After finishing, I remained near the ramp, listening to music. I glanced to my left and saw a group of 3 white women staring at me, conversing in hushed voices, and knew exactly what they were thinking.

Terrorist.

As a Chicano, I’m quite familiar with the look of disdain that I tend to garner from whites. It’s one of those daily occurrences that people of color are all too familiar with; the stare followed by those silent musings of racist thought. It happens, we process it, and typically we just move on with our day, cataloguing it in our index of white supremacy experience.

As the bright headlight of the train began to shimmer on the horizon, I saw a female officer come up the stairs and walk over to the group of women. They talked about something amusing, as the group laughed lightly at the officer’s comments. Then one of the women pointed directly at me, and the officer walked my way.

Damn, I thought. Damn I should have waited until I got home.

Her conversation with me was casual, mentioning the weather and noting the recent chill in Southern California.

Go ahead. Just say it.

“So are you visiting town?”

“Yes, just visiting a friend,” I replied.

I know you’re going to ask, why are you pretending to talk me up?

“Do you live in LA?”

“Yes.”

At this point the train was less than a minute from arriving at the station. “Have you been waiting here long for the train?”

“Yeah, since noon. It’s running about 20 minutes late. But it’s here now.”

I began walking towards the train, praying that this moment would contradict my instinct, would run counter to the experience of people of color, of Muslims living in this country.

“Hold on. We got a call about a suspicious person walking on the tracks who fits your description.”

When you realize that you’re being racially profiled, that feeling of xenophobia and white supremacy is going to disrupt your very existence, causing anger to boil swiftly. It builds up from the gut and travels instantaneously to your brain, and then to your mouth.

“This is bullshit,” I said. “Those women called the cops because I’m Muslim and I was praying. I was nowhere near the tracks.” I pointed to the area where I prayed and told her to check any of the security cameras. I have to admit, I was surprised that her facial expression changed to one of sympathy and understanding. Maybe it was because she was a woman of color, and in that moment, her position as a law enforcement official was superseded by her position as both a woman and a person of color, who had confronted white supremacy in countless ways throughout her own life.

“Oh,” she said. I walked towards the entryway of the train and she didn’t follow.

I turned back to make sure that this wasn’t seen as an act of defiance or resistance, to confirm that she was ok with me entering that train. Again, this is a reality that folks of color must confront; a mistake as simple as walking away can lead to us getting shot. Two white male officers bounded up the stairs, ran towards me, and told me to wait.

My anger at this point escalated, knowing that I was very likely not to receive the same glance of sympathy from these officers. The barrage of questions began: where are you from, do you live here, were you ever on the tracks, what country are you from? Each one reeked of white hegemony and xenophobia, stung with bigotry and ignorance. Again I repeated, “You got a call because I’m Muslim and I was praying. Security tapes can confirm this. Pull the racist white women off the train, have them try and explain their racist lies.”

“I cannot miss this train, I cannot miss this train, I cannot miss this train,” I repeated.

I was allowed to board the train after a couple more minutes of questions, and pressure from the conductor that he needed to leave.

—–

I’ve only been ‘officially’ Muslim for just over three months. Three months, and I’ve already been profiled. Imagine this multiplied by decades, centuries. Muslims in this country are racially abused every day. We’re attacked when we pray, we’re attacked as activists against the Israeli occupation of Palestine, we’re profiled while traveling, and we’re the unjust victims of a misguided and racist war on terror. This racial animosity is even extending to our Sikh brothers and sisters, who are being attacked and killed because bigots think they’re Muslims. The actions of a small, marginal group are being collectively punished through these acts of racial profiling and xenophobia. We’ve become a target because we’re allegedly the biggest threat to the American people.

Nevermind that the overwhelming majority of mass terrorist attacks (which is what mass shootings are) in the years since 9/11 have been committed by white males. Nevermind that numerous advocacy groups and government reports have shown that right-wing, white terrorism is responsible for the majority of terrorist incidents in this country since the Oklahoma City bombings in 1995. Yet, it seems that America doesn’t follow it’s own pattern of racial exclusion when it’s “attacked.” They labeled native Mexicans as terrorists during westward expansion and the battle for the Alamo. They gathered up and interned the Japanese during WWII. Yet white supremacy won’t allow for this country to profile it’s own, despite the clear evidence. It’s easier for America to place the blame at the feet of the “Other.”

It’s important that we, as a religious community, are allowed to practice our religion freely, and not feel like we have to weigh the possibility of physical or emotional harm against our desire to pray. To pray. Safely and without harm. My decision to pray publicly is not only my way of showing remembrance and submission to Allah (SWT). It has become, for many of us, a political act. An act of solidarity for the countless Muslims we see and don’t see, who also pray in public—an act of solidarity for those who don’t feel safe enough to pray publicly. Maybe seeing one or several of us praying publicly will be the push for someone else to feel more comfortable exercising their right to express their religious beliefs. I’ve even seen public prayer be a moment of education for those not familiar with Islam.

It is not a criminal act.

So the next time you see a Muslim praying in public, please don’t call the cops.

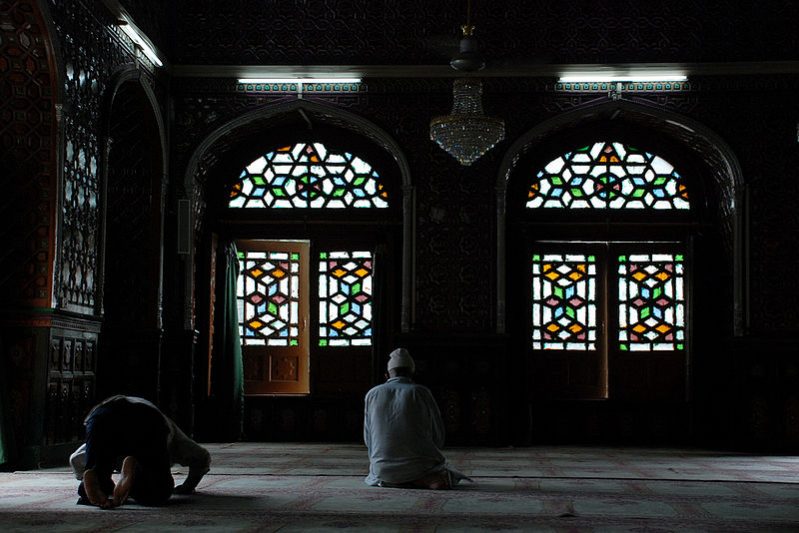

Featured photo: “Prayer,” © 2009 Irumge, used under a Creative Commons Attribution license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

Very nice article. Thank you for sharing and bringing awareness.

I’ve prayed at this train station and pray in public regularly. I live and work in the Tustin area and am surprised that this incident happened here, it’s fairly cosmopolitan and there are so many Muslims around. I’m happy you weren’t delayed and a bigger issue wasn’t made unnecessarily by the police. Remember your rights when it comes to law enforcement and always keep a calm patient tone. As much as we hate to be singled out it’s their job to respond to any perceived suspicious activity, which is lame because it is ignorance that equates our praying with anything sinister. Our job as a community needs to be to help educate local law enforcement on matters like prayer and basic Islam 101. Some of the organizers of the Tustin Masjid are UCLA alumni. I will meet with them and see if they can help educate the local police department as a first step. I admire your faith and courage.

As-salaamu ‘aleykum,

I could not help, brother, but notice that your article is overladen with references to race at the beginning, middle, end, and all points in-between. Yet the article is ostensibly about a negative experience brought about by peoples’ reaction to you praying salat.

You siad, “I’ve only been ‘officially’ Muslim for just over three months. Three months, and I’ve already been profiled.” Two sentences later you wrote, “Muslims in this country are racially abused every day.” Presumably your “race” did not change when you reverted. I know mine did not.

Islam is not a race. There are millions of Muslims who are neither brown nor black, and there have been for centuries. To imply, therefore, as is done throughout this piece, that the treatment you received–especially considering that the initial accosting officer was herself a woman of color–was based on race might be seen by some as a conflation of separate issues. You have mentioned the word “race” or described the race of others no fewer than twenty-five times in this piece.

The “fearful pit” you describe as “one that black and brown folks get when they see a police cruiser pull up behind their cars or slowly roll along next to them when they walk down the block” is also felt by white folks when subjected to the same police scrutiny.

I am Muslim, and white (and, like you, have had the experience of praying in public a lot). I was stopped by police last Sha’ban on my way to meet the rest of the Masjid at East Campus and look for the moon to see whether it would be Ramadan the next day. I was detained for almost an hour, endured all manner of drilling and attempted manipulation by the police, and at the end was told, not to join the rest of my community, but to go home by a very specific route which took me way out of my way. To this day my pulse increases and my temperature rises just remembering it. Alhamdulillah I was able to be pleasant with the officers while exercising my rights firmly, even though I was furious with the entire debacle. You are fortunate that you were not arrested after losing your temper.

Wa Alaikum As Salaam, brother, thank you for your reply. The reason for the mention of race and Islam in the post is because in the US, Islam has been racialized. Brown and bearded is the unfortunate stereotype of a Muslim in this country. I am very well aware that Islam is not a race; America, unfortunately, is not aware of this fact. My interaction with the first officer to arrive on scene is not evidence that race isn’t an issue; the real issue is who called law enforcement to report me. The mention of the women was because, in my interaction with her, I perceived understanding from her perspective.

I would also argue that the fear that People of Color feel when encountering law enforcement is both greater and qualitatively different. As a white male, you can take comfort in knowing you overwhelmingly face much smaller chances of getting beat or shot by a police officer. I don’t think that there is any denying this; police brutality is, effectively, not a huge issue that whites fear. That’s not to say there is an absence of fear, but I would argue that the vast majority of whites do not hold the same fear that Black and Brown folks in this country face.

I’m sorry to hear of your difficulties last Ramadan. Fear of Islam has the potential to affect all Muslims, regardless of race/ethnicity. However, I don’t think it could be said that white Muslims experience the same level of prejudice and harassment that Brown Muslims do.

Lastly, your last statement is a bit misguided and frankly, a little off-base, my brother. I am well aware of the danger of losing my temper. Patronizing me for it seems a bit much. Salaam, my brother.

Allahumma fa’ayyumaa mu’minin sababtuhu faj’al dhaalika lahu qurbatan ‘ilayka yawm al-qiyaamati.

You’re so interesting! I don’t think I have read anything like this before. So wonderful to discover somebody with some unique thoughts on this subject matter. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This website is one thing that is needed on the internet, someone with a bit of originality! dgdcfbegkkdaeakk