USC just set an alarming precedent in academia.

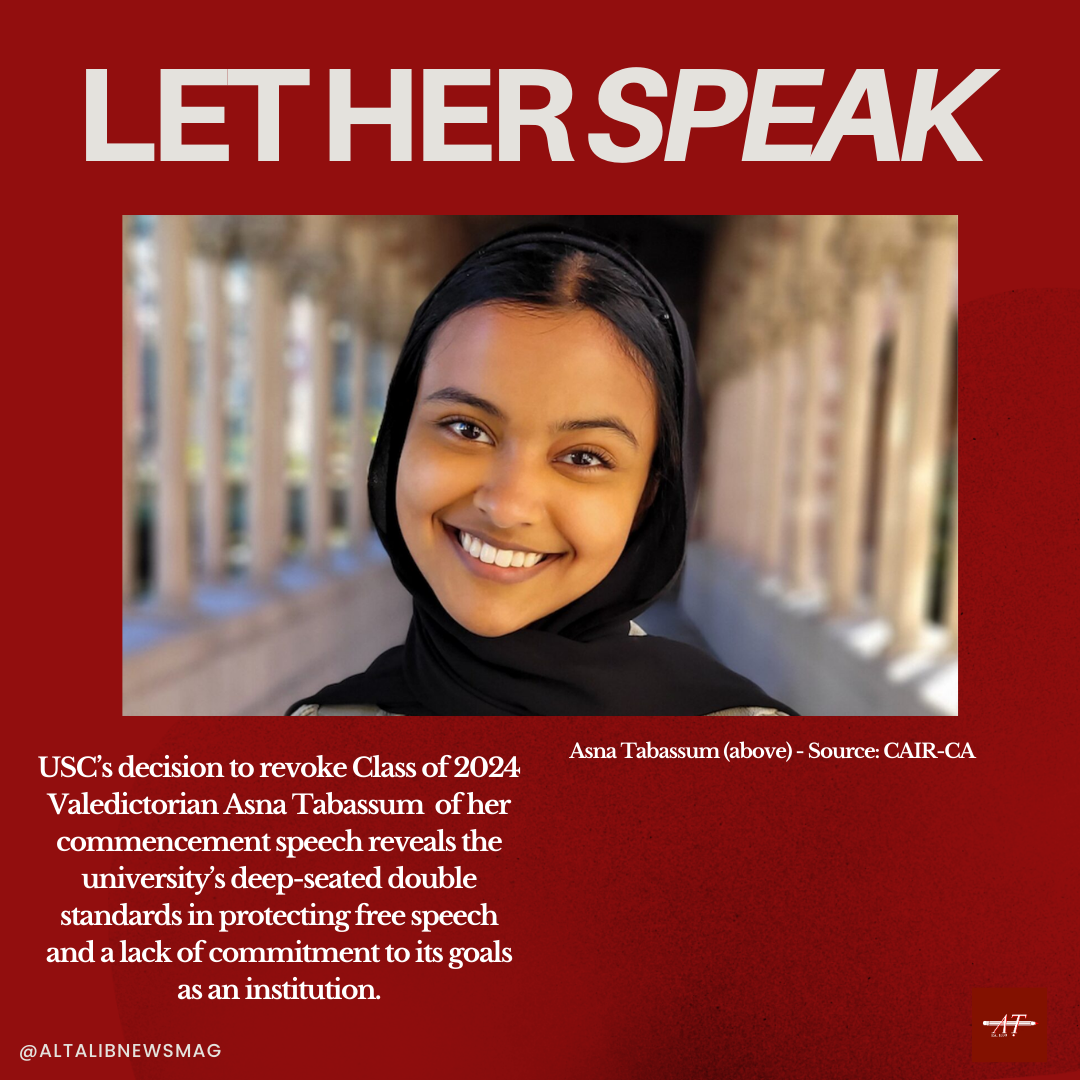

On April 15, 2024, Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Andrew Guzman announced that their class valedictorian, Asna Tabassum, will not be delivering a speech at this year’s upcoming commencement. The administration cites safety concerns stemming from ongoing political tensions amid months of atrocities and violations of international law afflicted on Palestinian civilians in Gaza.

Words cannot begin to describe the double standard the administration has imposed on its student body–raising multiple questions for any mild skeptic. To be sure, USC’s decision is motivated by the need to protect. But who is being protected? And what for?

In response to these questions, Guzman writes: “While this [the decision] is disappointing, tradition must give way to safety. This decision is not only necessary to maintain the safety of our campus and students but is consistent with the fundamental legal obligation–including the expectations of federal regulators–that universities act to protect students and keep our campus community safe.”

While noble at first glance, these statements ring hollow when considering the institution’s presumed need for elevated security at various other occasions. The administration undoubtedly elevated security measures when President Obama attended his daughter’s commencement just last year. They also provided additional personnel when Ben Shapiro delivered a speech at the Bovard Auditorium in 2018–citing that public safety need not conflict with free speech. The decision also fails to consider alternate solutions that, if enacted, can provide Tabassum with the same opportunity to speak. They could, for example, livestream or pre-record the speech from a separate on-campus location and replay it for the audience on commencement. There are countless options to give Tabassum the voice she has earned through her years of dedication and academic triumph.

So, is USC unable to secure the grounds for Tabassum to speak, or are they simply choosing not to?

By silencing Tabassum’s speech, the university has instead opted to protect their reputation from criticism of views deemed unpalatable in the political mainstream–nevermind the fact that taking a stand against Israel’s humanitarian crimes can even be interpreted in a negative light.

Guzman insists that freedom of speech is not an issue in rendering this decision, writing as follows: “To be clear: this decision has nothing to do with freedom of speech. There is no free-speech entitlement to speak at a commencement. The issue here is how best to maintain campus security and safety, period.”

But Guzman is wrong, to put it generously. In superseding years of tradition, the decision has everything to do with freedom of speech. Even if no such entitlement to speak exists, as Guzman asserts, the fact that the administration chose to silence Tabassum entails that certain views are not as worthy of protection as others. Perhaps the administration believes that providing elevated security for her speech amounts to a tacit endorsement of the “controversial” view that Israel is violating international law in its mass destruction of civilian infrastructure and life in Gaza. Whatever the reason is, stated or unstated, the underlying assumption is that Tabassum’s beliefs are not worth enough to warrant additional protection that has been afforded countless times to other speakers–some of whom with views actually worthy of our condemnation.

But it goes even deeper than that. The decision is an affront to academic freedom and the values that come with it. It is antithetical to provide students with unique academic programs to specialize in but strip them of any platform to draw from those invaluable experiences. The irony becomes even more clear when assessing Tabassum’s academic background.

The university offers students a minor in “resistance to genocide,” an interdisciplinary program that focuses on the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, and atrocities afflicted on Native Americans through the lens of global ethnic politics, literature, and mass media. The program, at its core, is meant “to understand its [genocide] history—the factors that have brought it about and those that have enabled people to prevent, resist or recuperate from mass violence.”

Not only has Tabassum completed her minor in resistance to genocide, she has also gone to extensive lengths to conduct acts of service for marginalized groups. In a statement released by the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), Tabassum writes that the university gave her the opportunity to ship medical gowns to Ukraine, write about the Rwandan genocide, and provide medical assistance to the impoverished in Skid Row. All of these contextual factors speak to a character both unimpeachable and worthy of the mantle to speak amongst her peers on commencement day. And yet, here we are.

With this perspective in mind, why would anyone arguing in good faith question Tabassum’s commitment to justice for all marginalized groups?

Why would anyone, with this context, believe that Tabassum is anti-Semitic and insists on the elimination of other historically marginalized groups? Her experiences in her academic life, as illustrated, quite literally speak to the opposite.

If students cannot even talk about their formative experiences in a program such as “resistance to genocide,” why even offer students the program in the first place?

Academic institutions are meant to embody free speech and empower their students and faculty to challenge conventional narratives. To shun Tabassum of the opportunity to do so–solely on the basis of the presumed content of her speech–merely reinforces the pressures for Muslims and minority groups to conform to an established standard and strip themselves of their valued identities.

In closing the CAIR statement, Tabassum reminds us of the purpose her speech is meant to fulfill:

“I challenge us to respond to ideological discomfort with dialogue and learning, not bigotry and censorship. And I urge us to see past our deepest fears and recognize the need to support justice for all people, including the Palestinian people.”

Her speech is meant to convey hope for a better world that empowers everyone. But with USC’s decision, only one thing has been made clear: hope can only be offered to those deemed worthy in America’s warped political climate.

Reverse the decision, and let her speak.